Laundry Life

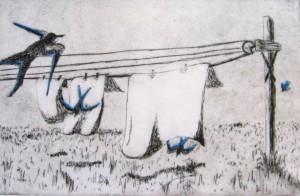

Monday morning is coffee smells and pulley squeaks

as my mother hangs clothes on two steel lines,

strung garden-length;

wooden pegs in a pouch on the line, the next peg

in her mouth – she could even talk around it.

First pinned are sheets and towels, then pants and skirts

pulled out to dangle over the tomato plants

at the back of the yard.

Shirts and blouses next, collars down

so shoulders dry without a mark. Underwear

(never bras!) hang close to the house, almost hidden

behind the vine-covered breakfast room wall.

Socks line up just so, toes point in one direction

(The days the heels and toes face each

other is a sure sign of trouble brewing.)

Rainy day lines criss-cross the open basement beams

over a hand-cranked mangle, steamy laundry tubs

and perspiring (not sweaty) mothers.

We kids peer in the neighbour’s window

to an identical scene, rest chins on the sill at driveway level,

yellow boots and knobby knees leave dry patches

on the pavement, along with the news from our side

kids were out in all weather

as long as they were together

Sheets hang blinding white in sunny winter rows,

dry stiff as boards, crack down the middle in a perfect

fold. My sister and I snicker

at the ossified pajama legs and other unseemly juttings.

We carry them under our arms into the house

to thaw over radiators.

The smell of frost and sunshine lingers

as they droop to the floor.

Waitressing to earn my university fees

between meals, I help the laundress string

long rows of flopping sheets

behind Monhegan’s Island Inn. Out of sight

of strolling guests the ropes stretch—salt would rust metal.

Long beach towels brush the grass,

their coloured curves, white fringed borders mirror

ocean waves that glint and foam along the shore.

I beg a corner of the line for uniforms, socks and “smalls”

hard to dry in my small dorm room.

Newly wed, our below-ground city apartment

boasts no green or cellar spaces. A tangle of ropes

stretched on a wooden frame in the bathtub

behind closed doors collapses without warning

under the weight of dripping hand-wrung garments.

Celebrating our eagerly awaited intimacy and freedom,

who cares? Until the baby came. I learned to drive

an old English mini, baby buckled in beside laundry

heaped high in the back seat.

I rattle up Spadina’s red cobbles to new machines

beside my mother’s basement laundry tubs.

Wash three loads, hang out, take in, hang out,

fold and fold and fold, catch up on family news,

neighbourhood gossip. Grandma and baby play,

cook a second-helping-of-meat dinner. Good trade.

A new baby on the way. We look

for a new home where children can play

And parents claim a toy free corner. Find a hot little

down-payment boosted house from parental pockets.

A big garden backs onto a stream (for now),

suburban women chat across fences, laundry placed

neat on “roundabouts.”

Plastic lines in four-square metal frames,

placed careful for the wind to find drying room,

quiver with diapers, sleepers (two sizes now),

man shirts (collars down) in every straight-edged garden.

Back to the city (I said it was more children

a third is imminent) but no libraries or book stores,

no trees or art galleries, drove me crazy.

A creaky old house on a shady curved street. A washer

and dryer. No clothes shall hang below in the basement,

no roundabouts allowed in city gardens. We work

behind shiny painted doors. I never liked the neighbourhood.

No children peered in the windows.

The relief of Haliburton summers! Ropes strung on branches

between trees, sag under bathing suits, towels speckled with pollen,

insects fly into them, snagged unawares in the dappled sun.

We travel through two lakes and up the river to town

in the big dorry once a week.

Sheets, machine-dried while we shop, are piled

beside bulging bags as four small chins drip ice cream

down their shirts. Lake smells

scent the beds for a night or two.

A marriage behind me with twenty-two years to sort:

what to keep, what else to leave behind? Move on

to a small detached, a friendly front verandah,

with two steel lines strung garden length from porch

to fence

by John, the youngest one,

the other children on their own. I dream

new gardens, hang a weekly laundry

with plastic pegs from the pouch on the line,

talk around the one in my mouth as new neighbours

air the week’s news.

Children grown—a stacked town-house,

a stacked washer/dryer in a cupboard,

the shower rod my laundry line for “hang to dry”.

Socks droop over water heater pipes,

sweaters on a towel drape over the toilet seat,

or lie flat in the bathtub.

On a good day

clothes dangle over chairs and plastic covered metal rods,

the old wood drying rack re-incarnated, out of sight

behind the gate and the climbing hydrangea

in my patio haven. Until

John’s spring-time death. Scoured to the marrow, stripped

root and branch, flesh folds carefully over fragile bone.

No gardens.

No life- line

anywhere spreads everywhere endlessly ahead.

I take refuge

in the land and lakes of the Manitoulin,

stretch out on grass, rock or dock. Floating on the water

suspended between earth and sky, I watch a contrail

cleave the entrails of gunpowder clouds.

What origin propels? What path re-orients a destination?

When the light has changed colour, the horizon

disappeared and the world is unrecognizable.

I write to hear my heart, to feel my breath

salvage body and mind

unearth roots

redeem passion