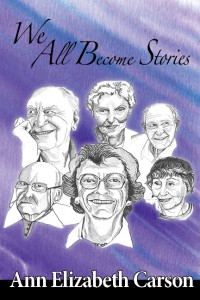

By Ann Elizabeth Carson

Illustrations by Jennifer Kenneally

Foreword by Dr. Ellen B. Ryan

Blue Denim Press, 2013

Available online through Amazon.com >

We All Become Stories appeals to our powerful, yet often anxious, curiosity about aging, memory and what lies ahead for all of us. We’re surrounded by books about aging – the aging brain, ageism, caring for aging family members, financial planning, health and aging, sex and aging, and so on. But these works rarely include the voices of older people themselves.

Ann Elizabeth Carson’s new book does just that. For over 30 years she has spoken with dozens of older people – learning, aging and growing along with them. Now she captures and describes the experience of aging through the life stories of 12 elders who made extraordinary changes in their lives to find places for themselves in societies that seldom welcome or respect old age. Through storytelling, conversations with her subjects and poetry, Carson reframes aging and old age as a fascinating, rewarding, and yes, hard stage of life that brings benefits and insights that aren’t available to the young.

Carson met many of her storytellers, such as Alice, Martha and Lev, on a remote island 40 kilometres off the coast of Maine. Others were family friends or participants in the workshops she led on memory strategies: artists, blue-collar workers, clerks, a housewife, a furniture maker and teachers. None are famous; all are searching for ways to live satisfying lives in their old age. Alice, at 89, “regiments” her life to conserve her energy and passion for painting. Martha learns that loss can “walk beside” her, with comfort an unexpected outcome, while Lev is surprised that isolation focuses his ”juice of life” into ever more beautiful work.

The elders harbour few illusions: life, aging and old age are tough, “a tall order,” as Meyer says, more difficult for those not used to “looking within.” They uncover remarkable restorative powers in continually reshaping themselves; they value independence and community, and they fear intellectual decline and memory loss far more than physical aging or pain. Exploring these themes led to the book’s three major insights: how memory changes at every stage of life, the difficulty of maintaining identity in a culture of stereotypes about aging, and how the sensory is indispensable to our understanding, our memory and our enjoyment of life-and of aging.

We All Become Stories speaks to us because it reveals how “aging” is not something that happens just to the already old, but is a lifelong evolution – a journey of self-discovery that is open to everyone. As Carson writes, “You begin to see that you can truly welcome old age when you learn about it from people you have come to know and value.”

Forthcoming: Canadian Woman Studies Journal, Trudy Medcalf, Review of We All Become Stories >

The Elders Introduce Themselves

Alice’s secret for a satisfying old age is to “Keep on doing what you love to do.”

A painter from her earliest days, Alice’s story is one of lifelong training and transformation. Married young and raising a son, Alice turned the domestic art of china painting learned in childhood into a profession as a landscape painter and respected art teacher. She trained her eye to see and remember the world in pictures, first through an art school framework, then gradually refined into her unique “Ashcan School” vision. At 89 Alice keeps on redefining her priorities so that she can participate in and be acknowledged by a younger arts community, and use her energy doing what she wants to do –paint.

Click here to read Alice’s Story.

Russell told me that “the one big tragedy of my childhood .. the tragedy of my life .. was being dyslexic.”

Russell’s house was the only one on Monhegan not muted to grey by wind and sea-salt. Bright pink, it stands against rock, an exclamation, visible in all weather. Laundry flapped above on a drying rack anchored in a small patch of grass in the rocks. One day, after a not-too-tiring or -sweaty hike, I noticed a sign beside the door: “Carina House, 2:00–4:30 Weekdays Only,” and decided to stop by. Bells on the screen door jangled as I stepped down into the small, bright kitchen crammed with a neatly arranged clutter of crockery and utensils — for Russell’s home, “too much is not enough.”

Click here to read Russell’s Story.

Martha: “Now I understand why I did certain things, I can accept more.”

Whenever I reach Monhegan Island I watch for her as the Laura B. out of Port Clyde, Maine nears the dock at low tide. Short, slight, dressed usually in red and blue, with salt-and-pepper hair moistly curling in the early morning mist under her round-brimmed white hat, she smiles broadly as we draw closer. Conversation on shore and aboard the boat stops in anticipation of landing, and I hear her soft, southern drawl: “I thought this day would never come.” Up the steep gangplank, I am finally ashore. And then we hug, lightly. It has been a while, but lightly is enough for old bones.

Click here to read Martha’s Story.

Miriam: “ We are made up of the times we are born into … Keep old friends and make new ones — human relationships are the nuts and bolts of everyday life.”

I see Miriam every Thursday morning when the catch arrives fresh at Monhegan Island’s Fish House, a small grey shack tucked in a sheltered corner on the harbour shore. A short, attractive, older, grey-haired woman, she always smiles, and eventually we chat a little, and then, at my request, she shows me how to choose the best fish. She was an immigrant child of the Depression, and poor. Her father studied Torah and had to talk to girls (since there was no son). Her mother was breadwinner and homemaker, her older sister competitive and manipulative. She learned how to “mind her Ps and Qs,” watching every move they made, listening to their every word, learning empathy through “being attentive to the person” so that she could judge how to get her needs met … and satisfy the needs of others.

Click here to read Miriam’s Story.

Meyer: “Are you learning something? Nature is my teacher now.”

I heard Meyer before I met him, playing piano at one of Monhegan’s evening singsongs. Hunched over the keyboard, head jutting forward in concentration, his long bony legs are clad in narrow black trousers, and his elbows are thrust up on either side so that his sweatered arms are like wings unfolding. He shoots a quick, quizzical glance over his shoulder as his fingers ripple a change in the music from his own composition to one that the audience, sitting in chairs or cushions around the fire, can sing. I often met him on Monhegan’s only road — tall, gangly, sporting a pork-pie hat over a fringe of grey hair. He needed a leg brace and walked with a cane, limping a little, a shopping bag in his other hand, looking around as if he were seeing the houses and gardens for the first time.

Click here to read Meyer’s Story.

Callum: “ The sensory is the foundation of experience and memory and you cannot talk yourself out of that.”

Dressed always in khaki, the colour of his hair, I can see Callum Brookes as part of the Mexican sand (where he and Charlotte Selver taught in the winter) in the same way that he merges with the colour of Monhegan’s dirt road as he makes his way to the post office or grocery store — sites of forgetting — or accompanies Charlotte, holding her arm, head tilted to the right in conversation. Slim and short, he moves economically, and his wide blue eyes meet mine directly when we speak, often with a mischievous twinkle when he thinks we are “getting too solemn about serious topics.”

Click here to read Callum’s Story.

Rebecca: “The life I had, good or bad, I gave it to myself.”

It’s late fall and Rebecca wears an elegantly casual black coat, a touch of red in scarf and gloves. Almost black eyes and cropped, dark brown hair curling a little around aquiline features speak of Sephardic origins. Settling in with coffee in the lounge of the senior’s centre where I had taught a course in memory strategies Rebecca begins by telling me that her early life “was tough from the beginning.” The second oldest in a European Jewish immigrant family of six — three daughters and three sons — she started taking care of her younger brothers when she was very young. She was 15 when the third one was born, and her mother, knowing that she was crazy about the kids, “gave him to me: ‘Here,’ she said, ‘this one is yours.’ To this day he feels like I am his Mom.”

Click here to read Rebecca’s Story.

Lev: “With every loss there is a gain, and contrariwise.”

Walk up the gravel road past the four corners where the church, the post office, the Monhegan House Inn, and the general store meet. The road narrows, the stones are bigger, ready to trip over; wild roses fence in houses on either side. There’s a big red-painted house on the left as you turn a corner, and on your right a sign points up a hill to the hostel. That’s the last building you’ll see before the painter Wyeth’s house, high on a cliff looking over the ocean and the rusty-ribbed shipwreck keeled over near shore.

Click here to read Lev’s Story.

Emma: “Plan ahead – then change won’t come as a shock.”

Emma remembers Queen Victoria in her horse-drawn carriage and her frail, black-gloved hand waving acknowledgment to the people cheering her Diamond Jubilee, and waving her own small two-year-old hand.

“I remember all the way back. An actress friend of mine said that if I can do that, I must have total recall.” Emma says: “You see, everything has a sound, a picture: I can hear the clucking of my mother’s chickens riding on the roof of the carriage on the way to our new home in Sheffield. It was the one possession she insisted on taking.”

I remember her telling me: “I can’t play the piano, but I can still listen to music. I won’t hear all of it, but I will hear it in my mind. I don’t read much anymore, but I can still recite poetry (mostly to myself; there aren’t too many who have been brought up to enjoy it). I can still envision all that I saw in my travels and enjoy nature. When I can’t get out, I watch the birds at the feeder.”

Click here to read Emma’s Story.

Rivka: “It’s never too late, I feel myself so differently. I am better now.”

She sits bolt upright in a corner of the lounge at the Jewish seniors’ centre in North Toronto: short, plump, grey-haired, hands clenched on her lap, her face strained. Gradually, as she sees that I am not pushing her to talk about anything she doesn’t want to she tells me that she usually avoids thinking about the past because those memories are too painful.

She was raised in poverty in Winnipeg during the depression of the 30′s: “The economic situation was very bad when we were children, problems of unemployment, strikes everywhere, the workers struggling and no one seemed to care. That may have something to do with it, or whether it just seems that you inherit it somehow. If you get that feeling—I hate to see anybody put down. And I had a strict father, he was a scholar and worked when he felt like it; it was my mother who always worked.”

Click here to read Rivka’s Story.

Avram: “Your life can seem over when you retire.”

When Avram retires from his position as a respected union organizer in the millinery trade from Montreal, he is convinced—and terrified—that he is losing his memory. It takes a lot of convincing during several conversations for him to believe that he can transfer his negotiating skills and well-honed memory strategies to his life after retirement. But he works at it and succeeds.

It was different when he was working. His union jobs—first in Montreal, then the war years, and afterwards Toronto—took him all over Ontario and Quebec troubleshooting, and he had to be on his toes. He’d meet people and think to himself, “‘OK, what’s the name, where did I see them, what were we doing?’ I didn’t have any trouble remembering then.”

Click here to read Avram’s Story.

Beatrice: “I have to be bolder than I ever was.”

“You’re wondering why I’m here.” She is sitting in the lobby of the nursing home.

“It doesn’t seem much like your kind of place,” I replied.

“Well, there was no choice. You see, after the accident I lost my sense of taste and stopped eating, it didn’t seem worthwhile. And if something spilled on the floor I couldn’t get down to clean it. Isobel came on weekends, but then she moved to Toronto with her children for a better job. I had a TV and radio with a tape recorder, a stereo, and lots of books, and I’d just sit there and cry. A social worker came to visit and said it was a depression, and I said, ‘To heck with this, I’ve got to move.’ That’s when I decided I wanted to live. I didn’t, after the accident; I wondered why I hadn’t died.”

Click here to read Beatrice’s Story.