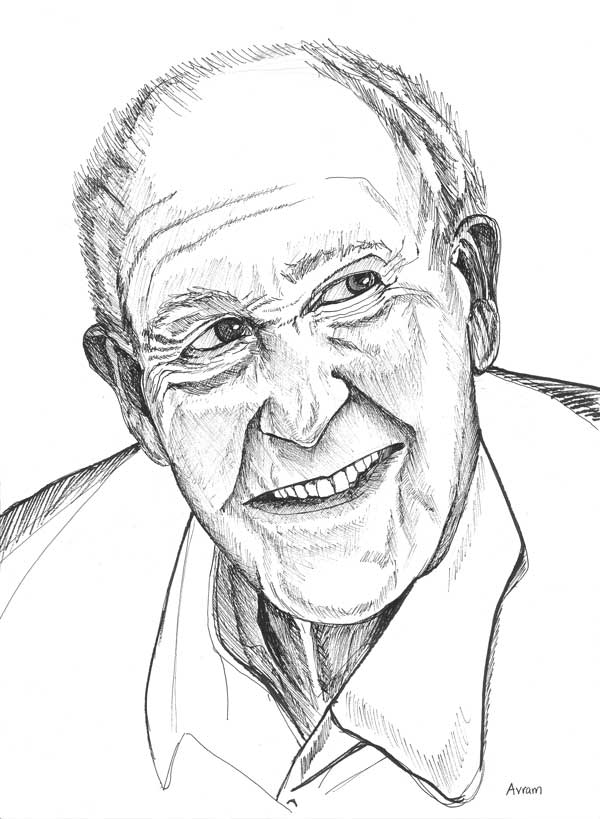

Avram: “ Your life can seem over when you retire.”

I realize that the socially separated worlds of work and home, mind and body, are woven together and are not as different as we usually think they are.

A Union Organizer Retools: Avram’s Story

It was different when he was working. His union jobs—first in Montreal, then the war years, and afterwards Toronto—took him all over Ontario and Quebec troubleshooting, and he had to be on his toes. He’d meet people and think to himself,

“‘OK, what’s the name, where did I see them, what were we doing?’ I didn’t have any trouble remembering then.”

“Because once you found the place, or what happened, the name came?” I ask.

“Oh yes. Because then, when I met them, I knew who they were. Before the meeting started someone would come over with a problem—there’s always a problem, whether it’s serious or not—and you’d talk. I never had to grope for that, like I do now.”

“How is it different now?”

“Maybe because it’s not the same kind of activity; no activity at all now, really.”

Avram recalled his union days vividly and in detail. I asked him why.

“What happened a week ago now is the same as this week or the week before and hard to recall, but when I was working I was in the middle of things, back and forth with everyone, keeping track of a hundred things, maintaining this, that and the other.”

He used different strategies depending on the situation, like threatening a strike if management refused to let the union see the books to verify contract wages—”they’d cheat every chance they got,” said Avram. And he was very savvy—developing good relationships with workers who climbed to middle management and were “willing to smooth the way.

“I had this one guy, used to be a carpenter, then he was foreman and would tip me off to what was happening on the floor so we could catch the situation before it got blown up. Then the manager he’d say to me, ‘Avram, What are you, a magician?’ And then he’d give me another problem, ‘Avram, I can’t get this nutball to do anything, use your discretion on that will you, he bugs me day in and day out.’ You had to be a psychiatrist sometimes to know where they were coming from.”

“You had to learn about people’s personalities, their quirks, so you could pull everything together,” I said.

“You bet, drove me almost crazy sometimes. But I loved the challenge. You had to understand the background, not just the immediate problem. Like the guy who came in drunk all the time because his wife was sick and in turmoil with him all the time about his drinking and how they couldn’t pay the bills. I told him I’d have a talk with the union president, how the guy couldn’t pay the rent. They paid the rent.”

Avram saw no challenge in retirement until one day I asked him if he’d ever talked with the director of the community centre where we’d had the memory workshop, about organizing and leading some of the groups they hold. He was quite surprised and said he didn’t think of himself as “being on that level,” with an incomplete high school education.

“Hey, Avram!” I replied. “You’re a problem solver, you’ve got all those people skills, you’re diplomatic, you’ve led plenty of groups, you speak three languages, and you’re used to all the emotions—people getting angry or upset—that can crop up, you can handle all that. I think you’d do a great job.”

“It’s an idea, I’ll think about it. I’d like to tackle something.”

Avram joined a life review group at Ryerson and went on to lead several groups at the seniors’ centre. The director was delighted. Now Avram is negotiating relationships and solving problems, “understanding the backgrounds of all sides, not just the immediate problem”—busy “maintaining this, that, and the other.”

After the workshop Avram wrote me a note: “Leading these groups has got me into a little reading, which I never had time for before. You probably know about this guy Doidge* but I didn’t and he sure has hit the nail on the head for me. He’s got these seven key points that once you remember them can be a big help with how you understand what’s going on in your life.”

1. Memory is critical to learning. Well that seems obvious. It’s just that once I was stuck at home what was there to learn?

2. Motivation and challenge alter the brain. What’s so challenging about being around home? I wasn’t so much in the mood to do anything there and had to get out. Once I got out I was OK.

3. Plasticity can be positive or negative. So, like I said you get stuck in a rut, like those coconuts at work who wouldn’t take on anything new. It’s like they had rusted brains.

4. Brains can change at all stages of life, so they are vulnerable to physical and emotional shock. I was sure stressed out with those stubborn guys arguing on all sides, and then with thinking I was losing it when I had to stop work.

5. Changes happen gradually. I guess it took me awhile to move into another level, but it doesn’t seem so different what I’m doing now than when I was working with the unions … everyone has their problems no matter what their stage in life.

6. Exercise assists brain change and learning: There’s a class at the centre. It’s not football, but I wouldn’t be too good at that now anyway. We go out afterwards for a coffee and to chew the fat, its’ almost like old times, like I used to do at the Ex., only with new heads.

7. Initially, changes in the brain are temporary; repetition is essential. I guess you get used to doing it and it’s like you always have. There’s a lot of stuff I don’t need anymore, but that doesn’t bother me now.

* Dr. Norman Doidge, The Brain That Changes Itself. See also Posit Science and Brain Fitness Gym websites.